|

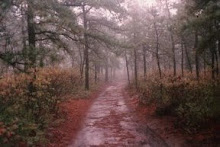

| Heading into the wild for the Hawk Circle winter survival trek. |

I have to add that there were many things missing in this article, including details about the types of gear he was carrying, his mental status, his family or relationship quality and other things that can come into play, like the weather at the time, and food choices or availability. It doesn't go into whether he had practiced and trained for this outing, or what his level of experience was and many more questions we all could think of to ask about this person and the specific circumstances of this tragedy.

In the short of it, that stuff doesn't matter. He died. He died trying to live off the land, and practice the same skills that many of teach and share every day. And that should sober us, and make us think long and hard about how we teach, how we practice, and how we prepare our students, who might someday try a similar sort of walkabout.

|

| The Cherry Valley Creek: So Peaceful and Tranquil, Yet Great Perils Lie for the Unwary! |

It's easy to dodge our responsibility, if we choose. "Hey, it's not one of my students. My students would never do that." I think it is natural for the first response to be one of defensiveness, to protect ourselves from any part of blame for this avoidable tragedy. I know that some of that was running through my head at first.

However, it leads me to thinking about how we inspire our students. I thought about how I was inspired, long ago, by my teachers, like Tom Brown, Jr, and John Stokes, and Jake Swamp. I thought about the ways they inspired me, and, at the same time, balanced that with appropriate cautions and warnings in the right amounts too. Tom used to say (and probably still does) that "the Earth will never hurt you, as long as you move and flow with it". I believed this statement, and still do, to a degree. But I also know that there are people who could take that statement and walk out the back door into the wilderness fully believing in it, and die a few hours later because they didn't really know what it meant, and they took that one statement out of context of a larger perspective and body of knowledge.

In other words, Tom spoke those words to us, as adults, and in the context of a full week of immersed learning and focused teachings. He knew we weren't going out the door at the end of the day, or couple of days, and he had time to share the full spectrum. I know, because while 20 percent of his teachings had this same type of beautiful, inspiring harmony, there was another 20-30 percent that lay in vivid stories and teaching that scared the crap out of me. It balanced out. It made it complete, and left me with days and nights lying in bed and going back and forth, always thinking things like: "Am I ready to go into the woods yet on my own, to live this philosophy?" "Have I practiced enough, to where it is reliable and a part of me?" and "what the heck does that mean, 'the Earth will never hurt me as long as I move and flow with it?' What is 'flow' anyway?"

|

| Brian Sullivan heads into the wild for a spring survival test. |

You can see, this topic is complex. It has a lot of threads, and has few easy answers. It is something I think about while working in our barn, mentally preparing for summer camp, or on the long drives through the rural New York countryside, heading to a meeting or after school program. In the past few weeks, I have come up with a couple of ideas so I thought I would lay them on you and see what you think.

First, and easiest, is to Balance Inspiration with Hazard Awareness. Give equal time to each area of your program, and tell stories on both ends. Yes, it is great to share the wonder of seeing an early sunrise on the banks of a river, or hike in the moonlight, or whatever. Those things are amazing and can help us feel like we are walking in the footsteps of the ancients. But it is important to also share stories of hypothermia, of adequate nutrition and caloric intake on a wilderness trek, especially for teens and young adults. You don't have to do it all at once, but make sure you do it. Seriously.

Second, make sure You are Modeling Safe Behavior. This means bringing a first aid kit on your treks and outings, and know how to use it. Get certified for CPR and all that, so you are trained up and professional. Wear warm clothing and gear when appropriate, and don't cut corners with safety in your programs. Bring flashlights and headlamps, and make sure all staff carry them as well, even on short day hikes, just in case. Bring warm clothes even on warm days, in case someone gets cold or immersed in cold water in an accident. Don't model behavior that could be dangerous in front of kids that could easily begin mimicking your actions in unsafe ways.

|

| Hawk Circle Assistant Director Randy Charles teaches students about respect for the bush. |

Fourth, Emphasize that there is Nothing Wrong with Using Back Up Gear while you are Learning. I think this is pretty self explanatory, but hey, I have to say it. And an addendum to this one is Watch out for The Crazy, Passionate, Over-Inspired Student! This is where your mentoring really has to kick in. You have to be willing to make sure that students are also modeling smart, safe behavior, and if they don't, then let them know they might not be able to stay in your program. Not as punishment for being inspired, but as a safety issue for other students. And for the safety issues for themselves.

In those situations, you have to find ways to get through to that person, not in front of the group where they might be embarrassed or feel self conscious, but at another time, discreetly, and have many as many conversations as necessary to help them value their own life, and others nearby. What will help is if you have developed a bond of trust, and if you communicate through that trust, and really listen to what they are saying, and hearing whether or not you are getting through. It takes time, and it isn't easy, but this is what we do. This is what makes us good and real and awesome.

|

| Ryan Smith cooks over an open fire on his wilderness skills intensive. |

Fifth, Be Sure to Praise Good Examples of Positive, Safe, Smart Behavior. Give credit to your staff. Give credit to the parents. Give awards to kids who don't get cut, or forget their rain coats, or whatever. I guess you can figure out what will work in your school or class, or camp or program. But it is true that what we focus on will get attention and lead to positive change.

I do think that over inspiration can be a real problem in some learning cultures in various wilderness schools, and the problem sometimes comes about because we, as instructors, like to share what got us into these skills, or way of life, and we share the same stories because it worked for us. However, we just sometimes forget about all of the other stories that were also shared at the same time as we were learning, or maybe our teachers never gave those to us in the first place. So we can just go through our teaching routines, and find the balance, and tone things down, and make the adjustments. It's not really all that hard, but the payoff is sweet.

I remember sharing some stories with a group of campers about one of my survival camp outs, telling them about the back up food I brought, and being huddled in a thick wool blanket in the early morning cold, leaning against a big pine tree and seeing the raccoons heading back to bed along the creek in the mist. I remember sharing about my army poncho, and how it kept me warm and dry in a massive, two hour downpour in the back country on a cold November evening. A year later, one of those same campers came back and shared her story, about how she remembered my wool blanket, and brought one along on her camping trip and was able to see deer pass within a few feet of her, on a morning where she would have had to leave early because it was just too cold for the clothing she had on. Kids listen. They understand, and they emulate. And when they have a success, they will know your teaching helped them have that experience, and it will be good. And those teachings will be passed down to the next generations, and so on.

Let's make sure we can pass on the best of our teachings to the kids of the future. Doesn't every student of ours deserve our best? And, if we do this, in a serious and deliberate way, the passing of this young Scottish man will not be for nothing. It will matter. It will make a difference.

Maybe his family would like that.

What do parents think?

What do students of the wilderness feel about this post?

What do you think?

6 comments:

Good food for thought, Ricardo. I agree with a lot of what you say. The East Shield (of Jon Young's 8 Shield Model) is the balance between hazards, awareness, and inspiration. They are all tied together. These are all essential at the START of a program. While I think it is crucial to impart safety to our students, it is hard to say what someone will walk away with at the end of the day. We can do our best to practice and preach safety ethics. And we are teaching survival. We humans have such complacent, comfortable lives that it is understandable that people will want to test their limits. This is a tragic instance of that and reminds me of Christopher McCandless of Into the Wild. Thanks for sharing your thoughts.

Dan Corcoran

Thanks Dan. I agree that it is important at the start of a program, and it is important to make sure these points get emphasized so they aren't falling by the wayside.

It is true what you say, that people, once they are finished with your program or event, are on their own and can and will do whatever they choose to with the knowledge learned. We don't, as instructors, have any control over that, absolutely. But it is in our diligence to insure that these cautions and information about staying safe are integrated in our curriculum, so that we can go to sleep at night, knowing we didn't just inspire the heck out of someone, and then forget to tell them about the cautions....

I know the East Shield contains both inspiration and hazards, and it is that balance that must be emphasized. I have known many, many schools that get young people so inspired that they try to do too much, ie, eating plants that they really don't know how to tell the difference yet as to their real identity, (over excited and inspired, yes, but not really taught how to properly identify!) or those who are inspired to mentor but lack the understanding of how to keep a group of kids safe in a storm... etc, etc. This is what I am talking about, and yes, it can be tracked back to specific individuals who can leave an unintended 'wake' in their passing.

I certainly don't want to call anyone out, and I am just saying that I have seen this myself, and heard stories from other instructors, campers, students and parents and it is time for it to stop. At some point, there has to be accountability and we have to be real about what we are doing, how we are doing it, and evaluate a bit before more people end up getting hurt.

Camp kids shouldn't be getting six hours of diarrhea from incorrect gathering, or getting hypothermia, or whatever, while trying to learn wilderness skills and get close to the earth. When that is happening, we have to have serious talks with those responsible, and often times, it isn't the young counselor or instructor's fault, but at their mentor or teacher.

Awareness is a big responsibility, and my feeling is that if someone wants to start teaching and be part of this movement, they have to be ready to step up and discuss this stuff, in a respectful manner, in a way that can provide a good dialogue and effect positive change. That is my only purpose for my post, really.

Hey Dan,

I was just thinking of something, after rereading your post.

I know your school has the philosophy of the East Shield, with has to do with inspiration, awareness and hazards. The real question I have is, and this just a professional question: Do you or your community, have a plan in place to insure that individuals responsible for inspiring and creating hazard awareness teachings actually happens in your programs? Is there accountability in your instructor community and class environment? Whose job is it to review and update the staff as to current hazards according to season, issues such as weather or construction or other pertinent program changes?

I am wondering what your school does and how it ensures that these things actually end up happening, and for which programs? (All or some?)

I think the answers to these questions can help newly forming schools and long time existing schools to develop ongoing professional enhancement and improvement, not just in tracking or wilderness skill development, but also in better mentoring and teaching....

I hope all is well in your community and just offer this comment as an addendum to the blog post, so if you feel like commenting about your own policies, I am sure instructors and school directors would welcome your ideas, but that is totally up to you... Again, thanks for posting!

To mentor young men and teens with humbleness is not easy. Balancing stories that illustrate the power of wilderness survival skills with the hazards if the wilderness is vary important to me in my work.

I've lead at-risk teens in the back country and taught at various day camps and overnight camps. Knowing how to avoid hazards is foundational to outdoor education. Every Outdoor program should know their limits and what to avoid teaching to manage risk of injury. I would never encourage kids to pick and eat wild mushrooms because of the many poisonous look a likes. If you don't know how deep the water is don't jump in folks. If you can take to time to show vary safe way to use knifes don't use them. I think most people get this concept.

I find it helpful in mentoring folks in outdoor skills to set up situations that test one skills in a safe way. I believe when folks experience just how hard it is to make fire in the cold rain they gain a new respect and humbleness. To create a safe experience where kids especially can be wet and cold it is imperative to have a warm shelter near by, a big fire, proper gear, and accessibility to first aid to avoid cold weather related injuries and make it fun for the folks involved not a life or deaf experience.

Josh Roberts

I like your words about humbleness, Josh. The thing is, your program involves mentoring young people in wild skills over a year, as part of a homeschooler program, so you have the time to get to know people, students, etc and take them one step at a time, deeper and deeper into the work.

On the other hand, many instructors have students for just one day, or a weekend, or a week, and don't have the time to do much else besides get the fire started in those folks, and I can see that it can be very difficult to fit all of the stories and details in just a few hours....

So, it's a balance, and we all are doing the best we can. Thanks for your comment and enjoy the spring!

This superfood has the longest shelf life ever (it will outlast you)

First off, I want to make this clear: no, it's not Pemmican.

After some extra digging I managed to find more secrets that were almost lost to history. I'm more than happy to share them with you.

In The Lost Ways 2 you'll not only find out what this superfood is, you'll also discover all the survival skills necessary for any crisis, including a lot method of preserving meat for over a year without refrigeration and how to make the lost samurai super food. And much, much more.

==> Click here to see everything you'll find in The Lost Ways 2.

Post a Comment